Normalized Estimation Error Squared (NEES)

A desired property of a state estimator (e.g., the Kalman filter) is the ability to correctly indicate the quality of its estimate. This ability is called consistency of a state estimator and has a direct impact on the estimation error \( \tilde{\mathbf{x}}(k) \). In other words, an inconsistent state estimator does not provide the optimal result. A state estimator should be able to indicate the quality of the estimate correctly, because an increase in sample size leads to a growth in information content and the state estimate \( \hat{\mathbf{x}}(k) \) shall be as close as possible to the true state \( \mathbf{x}(k) \). This results from the requirement that a state estimator shall be unbiased. Mathematically speaking, this is expressed by the expected value of the estimation error \( \tilde{\mathbf{x}}(k) \) being zero \[ E [ \mathbf{x}(k) - \hat{\mathbf{x}}(k) ] = E [ \tilde{\mathbf{x}}(k) ] \overset{!}{=} 0 \]

and that the covariance matrix of the estimation error shall be equal to the covariance matrix \( \mathbf{P}(k|k) \) of the state estimator \[ E [ [\mathbf{x}(k) - \hat{\mathbf{x}}(k)] [\mathbf{x}(k) - \hat{\mathbf{x}}(k)]^T ] = E [ \tilde{\mathbf{x}}(k|k) \tilde{\mathbf{x}}(k|k)^T ] \overset{!}{=} \mathbf{P}(k|k) . \]

Checking the consistency of the state estimator can be done with a hypothesis test using the Normalized Estimation Error Squared (NEES) metric. For this purpose, a normalization of the estimation error \( \tilde{\mathbf{x}} \) and the error covariance matrix \( \mathbf{P} \) is performed

\[ \epsilon (k) = \tilde{\mathbf{x}}(k|k)^T \mathbf{P}(k|k)^{-1} \tilde{\mathbf{x}}(k|k) \ .\]

The quantity \( \epsilon (k) \) is chi-squared distributed with \( \text{dim}( \tilde{\mathbf{x}}(k)) = n_x \) degrees of freedom.

A brief explanation why chi-squared distributed: The sum of standard normally distributed squared random variables is chi-squared distributed. Under the assumption that \( \mathbf{x}(k) \) and \( \hat{\mathbf{x}}(k)\) are standard normally distributed random variables, the estimation error \( \tilde{\mathbf{x}} \) is a standard normal random variable, too. Consult Wikipedia for more details.

Hypothesis testing

A very useful property of \( \epsilon(k) \) is that the expectation is

\[E [ \epsilon(k) ] = n_x . \]

This can now be used to check whether a state estimator delivers consistent results, i.e. whether it correctly estimates the quality of its estimation. The hypothesis

\[ H_0 : \text{The estimation error $\hat{\mathbf{x}}(k)$ is consistent with the filters covariance matrix $\mathbf{P}(k)$} \]

is accepted if

\[ \epsilon (k) \in [r_1,r_2] . \]

The acceptance interval is chosen such that the probability \( P \) that \( H_0 \) is accepted is \( (1 - \alpha) \), i.e.

\[ P \{ \epsilon (k) \in [r_1,r_2] | H_0 \} = 1 - \alpha . \]

The confidence interval \( [r_1,r_2] \) can be calculated with the inverse cumulative distribution function \( F^{-1} \) of the chi-squared distribution

\[ r_1 = F^{-1} ( \frac{\alpha}{2}, n_x ), \ r_2 = F^{-1} ( 1- \frac{\alpha}{2}, n_x ) . \]

Analysis of the NEES

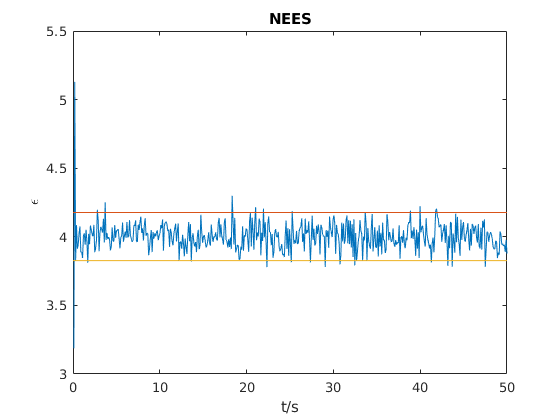

Most often, one can test the hypothesis by plotting the \( \text{NEES}( \epsilon(k) ) \) and the confidence interval \( [r_1,r_2] \) and check visually if the NEES is inside or outside.

Quantitatively, one counts the number of NEES values that are outside the confidence interval and sets them in relation to the total number of \( \epsilon(k) \). Formal speaking,

\[ \frac{1}{K} \sum_{ \forall k \in K : \epsilon(k) \in [r_1,r_2]} 1 < (1 - \alpha) \]

where \( K \in \mathbb{N}^+ \) is the maximum number of time steps, e.g. \( {1,2,…,K } \).

If the NEES is greater than the upper bound \( r_2 \), then the filter estimates the error to be lower than it is in reality. Provided that the measurement noise was selected properly, the process noise was chosen too low. If the NEES is smaller than \( r_1 \), then the error is estimated larger than it really is. In this case, the filter is called inefficient, meaning the process noise was chosen too large. In both cases, we can expect that an inconsistent state estimator will not reach the smallest possible estimation error.

Higher statistical significance

To increase statistical significance, additional \( N \) independent samples of \( \epsilon(k) \) can be generated and an average NEES can be formed

\[ \text{ANEES}( \epsilon_i(k) ) = \overline{\epsilon} (k) = \frac{1}{N} \sum^N_{i=1} \epsilon_i(k) . \]

\( \overline{\epsilon}\) has the property that the expectation converges towards \( n_x \) and that \( N \overline{\epsilon}\) is chi-squared distributed with \( N n_x \) degrees of freedom. The confidence interval must therefore be normalized by \( N\), i.e. \[ r_1 = \frac{1}{N} F^{-1} ( \frac{\alpha}{2},N n_x ), \ r_2 = \frac{1}{N} F^{-1} ( 1- \frac{\alpha}{2},N n_x ) . \] The hypothesis test is repeated in the same way as described above.

Conclusion

Obviously, the NEES is only correct in a “truth model simulation”, because the true state and the measurements are generated from the same system model with known statistical properties that the Kalman filter uses. It is therefore likely that a Kalman filter will pass the NEES hypothesis test within the simulation, but not in a real application. In practice, it is therefore recommended to perform the Normalized Innovation Squared (NIS) test exclusively or additionally to the NEES, because it does not require access to the true state vector. However, the NEES hypothesis test offers a deeper insight because the entire state vector is used and helps among other things in debugging within an application. This is based on the idea that if the implementation does not work correctly in a simulation with the “truth model”, why should it work in reality?

References

The textbook by Yaakov Bar-Shalom et al. Estimation with Applications to Tracking and Navigation: Theory, Algorithms and Software is an incredibly useful reference.

For more comprehensive insights, Salzmann’s work offers extensive explanations and further literature on this topic [1].

In our discussion on the performance analysis of Kalman filters, we refer to Mehra and Peschon’s 1971 work, which emphasizes the analysis of the innovation sequence in the time domain to assess filter efficiency [2].

The importance of the innovation sequence was first highlighted by Kalman in 1960, and further explored by Kailath in 1968, who showed that the entire filter could be derived from it [3].

This sequence also plays a crucial role in fault detection, as noted by Willsky in 1976 [4], and in adaptive filtering, as discussed in Chin’s 1979 survey [5].

Additionally, the statistical properties of the innovation sequence are verified using the Chi-square goodness-of-fit test to ensure normal distribution, as demonstrated by Bendat and Piersol in 1986 [6].

[1] Salzmann, Martin A. Some aspects of Kalman filtering. Fredericton, N.B: Dept. of Surveying Engineering, University of New Brunswick, 1988.

[2] Mehra, R.K., and J. Peschon (1971). An innovations approach to fault detection and diagnosis in dynamic systems. Automatica, Vol. 7, pp. 637-640.

[3] Kailath, T. (1968). An innovations approach to least-squares estimation Part I: Linear filtering in additive white noise. IEEE-Trans. on Automatic Control, Vol. IEEE-AC 13(6), pp.646-655.

[4] Willsky, A.S., (1976). A survey of design methods for failure detection in dynamic systems. Automatica, Vol12, pp.601-611.

[5] Chin, L. (1979). Advances in adaptive filtering. In: Control and Dynamic Systems, Vol. 15, Ed. C.T. Leondes, Academic Press, New York.

[6] Bendat, J.S. and A.G. Piersol (1986). Random Data: Analysis and Measurement Procedures. 2nd ed.,Wiley-Interscience, New York.